Every data manager working behind the scenes on a data catalogue or open data portal faces a different set of complexities and challenges.

- About Living Lakes Canada’s GIS and Database Manager

- Overview of hub’s challenges

- What is community-based water monitoring?

- The emergence of the Columbia Basin Water Hub

- Balancing the data quality and participation

- User control and data rights

- A look into the data submission process

- CKAN: helping power community based water monitoring

- Measuring impact

- What advice does Finkle-Aucoin offer for these groups and anyone else who is potentially starting their journey in managing a data portal?

About Living Lakes Canada’s GIS and Database Manager

One of these people is Maggie Finkle-Aucoin, GIS and Database Manager at Living Lakes Canada, and manager of the Columbia Water Basin Hub, a centralised on-line repository for water data collected from across the Basin. Built in partnership with Link Digital and launched in early 2021, it relies on the efforts of a large network of stewardship groups that undertake community-based water monitoring, the results of which are uploaded – often directly by the groups themselves – into the Hub.

For the past three years, Finkle-Aucoin has led the development and management of Hub, which helps communities across the Basin access and share information about their watersheds. She’s passionate about making water data more open, usable, and meaningful for the people who need it most.

We pride ourselves on being one on one with our contributors,’ says Finkle-Aucoin. We make sure that they feel comfortable, and that the data upload process is as easy as possible and as straightforward as possible, and CKAN [Comprehensive Knowledge Archive Network] has been really lovely to help us do that, because the back end is so intuitive for users. You don’t need to be a programmer to get your data into the Hub, which is nice.

Overview of hub’s challenges

But while the diversity of the Hub’s stakeholders is a great strength, it also presents challenges. These include ensuring data quality and standardisation, as well as dealing with a plethora of community-based groups with very different levels of data skills.

The following article will look at what the Hub does and the role CKAN plays within it, the value of community-based water monitoring, and how Hub staff like Finkle Aucoin balance community participation with running a technologically and socially sophisticated open data portal.

What is community-based water monitoring?

Living Lakes is a non-government organisation with 20 plus years’ experience working with community groups to protect freshwater within the Columbia Basin, North America’s fourth largest freshwater basin. It particularly focuses on elevating water science and stewardship through community-based water monitoring.

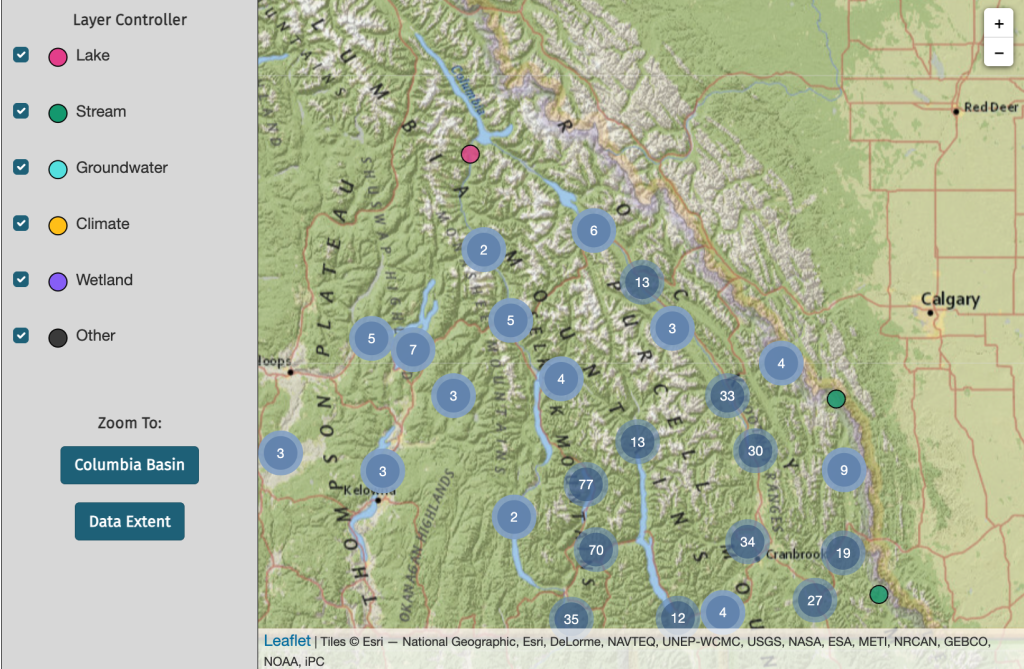

Community-based water monitoring refers to local communities actively collecting data on water quality or quantity. Living Lakes currently works with more than fifty groups, primarily community-based water monitoring organizations, but also including commercial interests, Indigenous groups, local conservation organizations, and river users such as fishers, hunters, and kayakers. Between them, these groups have contributed most of the 500 or so datasets currently hosted by the Hub.

In addition to filling gaps in water data collected by larger government bodies, Finkle-Aucoin maintains community-based water monitoring

strengthens water stewardship and empowers people who are involved in these types of initiatives to protect their fresh water sources and take back a little bit of power. This is achieved by connecting them to water planning and decision making and stewardship and research.

While local water monitoring had been going for many years prior to the Hub’s establishment, there were serious issues with how this data was being collected and stored. These became apparent during a series of meetings organised by Living Lakes in 2017, which brought together hydrologists from across British Columbia, to try and answer the question: was there enough data to understand the Columbia Basin’s health. The resounding answer from the meetings was no. While a multitude of local community groups were conducting water monitoring, they lacked streamlined archival and retrieval technologies for the data they collected.

The emergence of the Columbia Basin Water Hub

Another thing that came out of this was, where is this data going? Where is there a log of what is happening and who is monitoring it? So, that is where the Columbia Water Basin Hub was born, this idea that there needed to be a centralised repository for water data in the Columbia Basin, specifically. Because we knew monitoring was happening but there was no way to track down that data and what it was. It was mostly being held on private devices, in some cases, even paper, and it was at risk of being lost.

Balancing the data quality and participation

The Hub was designed not only to store past, current and future water data, but to ensure adequate quality control and make the data more accessible and shareable. While having a network of community-based water monitors is an incredible asset, it is not without challenges for those working behind the scenes on the Hub.

Not only are the groups doing water monitoring very diverse, so is the data they generate. This includes data on water quality, sustainable land use, changing weather conditions, ground water levels and reservoir modelling. The data is collected in different formats, making standardisation a challenge.

User control and data rights

Giving users the functionality to be able to directly upload their data was intentionally built into Hub’s design. All contributors sign a data sharing agreement outlining their rights and responsibilities, including the fact that even if it is hosted on the Hub, they are still the owner of the data and maintain full control of it, so they are also able to take down their data whenever they want. But while stakeholders can upload their data directly to the Hub, the various groups concerned have different data skill levels, which means not all of them are capable or want to do this.

The idea was initially that the Hub can be like a self-sustained data portal. So, we would make sure that users were able to contribute data and there wouldn’t be the need for someone like me to manage the portal. We laugh a little bit about this now because, even when users are able to upload their own data to the Hub, there is a need for that oversight and management over the portal.

A look into the data submission process

Data standardisation is obviously vital to making sure the data the Hub was ingesting is usable and machine readable. Apart from data skills, many of the groups doing water monitoring don’t have a lot of capacity and are already working on tight budgets, so to ask them to also take on tasks associated with data management can be a stretch. To get around this, Living Lakes helps community water monitoring groups to develop data management plans. And, if groups want to directly upload their data, Living Lakes also provides templates and will do a training session to provide them with the necessary skills to do so.

Or you can send us the data and we would manage the upload,” states Finkle-Aucoin. “Our team offers, basically, on a scale of zero involvement to a hundred. We have some contributors who, every month, [just] send us a raw data file straight from their logs and that is it.

The Living Lakes team behind the Hub go through all the data uploaded by users, including undertaking a rudimentary quality assurance and quality control on it.

Perhaps there might be metadata info missing, or we might need some site photos. Or can you provide us with a little information about the calibration of equipment? And one of the best things that we’ve seen about the Hub is that data across the Basin has improved. It’s been one of the hidden unanticipated benefits of the Hub, that the quality of the water data has gone up.

CKAN: helping power community based water monitoring

In addition to being open source, which was highly desirable, CKAN was chosen as the software backbone of the Hub because the British Columbia and national government run their databases primarily on CKAN platforms.

Database integration has been important for us from the beginning. So, we saw choosing CKAN as a strength for development down the road when we potentially hope to get some better integration set up between those databases and ourselves.

CKAN also helps Living Lakes support community-based water monitoring in other ways, including enabling the development of a standardised vocabulary which helps when people are uploading data and searching for it on the Hub. Finkle-Aucoin cites climate change as an example.

If someone is selecting a tag that says climate change, we want to make sure that the data it is generating is actually climate change data. And this is a good one for an example, because typically, everyone feels that all their data relates to climate change [because] it’s water. It’s the one they click every single time.

CKAN has [also] been really great because we’ve been able to get some tools in place that alert us whenever new data is uploaded so we can kick off our process of going through and making sure that things are kind of tackled as soon as possible.

Lastly, Living Lakes has been impressed with the intuitive, user-friend set up of CKAN. This makes the portal relatively easy to use for those with varying levels of technical expertise.

The way that we are able to standardise the metadata is a definite strength and the way that this has made it [the data] accessible to users. You don’t have to be a programming whiz to get data up there. We are also able to set the parameters of the metadata, really let users know what information we’re looking for, what we need from them to accompany their data and they’re able to input that in there and we can force their hand a little bit to make sure that they are selecting the right options.

Also read: How CKAN and FAIR Principles can enhance metadata management

Measuring impact

One of the most difficult jobs facing data managers is trying to measure the impact of their data catalogue or portal, and the Columbia Water Basin Hub is no exception.

Yes, measuring the impact is always one of the constant struggles. Obviously, it is our hope that people will reach out to us whenever they use our data but it’s not always the case,

said Finkle-Aucoin.

To get around this, Living Lakes undertakes outreach so that people know the site is there and what is on it, and to ask stakeholders, if they are using the data, how.

So much of our data, I think the largest portion of our data, is tabular data, which means very little to most folks. And our decision makers are not data analysts by any means. So, what we have done is we have set up meetings with different kinds of government officials. We try and make sure that as many people as possible know about the resources. We talk to the officials; we talk to their staff as well.

Data from the Hub has been integrated into numerous reports and the government has also used the data in areas such as licensing the use of certain water bodies and groundwater analysis. The Hub’s data is fully integrated with the Canadian Watershed Information Network, a spatial research data infrastructure system hosted at the University of Manitoba, and also registered with DataCite Canada, which means it has a Digital Object Identifier, which has been useful in terms of seeing where it is being cited.

According to Finkle-Aucoin, Living Lakes is also using the Hub’s data to create knowledge products through a Watershed Bulletin.

This is a project where we have taken our monitoring data and have transformed it using the idea of storytelling. So, for example, we’ve done one on groundwater data, one on hydrometric data, using the data that’s in the Hub, and creating stories around that data. This has been a really good way to get a new diverse audience’s eyes on the data that’s already been interpreted for them.

Conclusion

Future plans at the Hub include talking to groups and coalitions in watershed areas outside the Columbia Basin, about setting up their own data portals.

We actually have data from outside the Basin on our Hub because there isn’t an appropriate home for it elsewhere. So, we’ve been chatting with other watershed groups and coalitions of communities that might find benefit in having something similar to the Columbia Basin Water Hub and helping to facilitate those types of builds.

What advice does Finkle-Aucoin offer for these groups and anyone else who is potentially starting their journey in managing a data portal?

I think the one piece of advice that I would give is, find your niche. For example, with the Columbia Basin Water Hub, we knew there was a gap that we needed to fill, we understood what that gap was well. We understood what our users needed well, from the process of engaging with them and talking with them, knowing where their struggles are. But even more so, always keeping that listening ear open. We are constantly accepting feedback, and we’re always ready to adjust and change for our user groups… Because without our users and without our contributors, we wouldn’t have much to show.

You can also read: